Research VP Yvonne Harris ’84, M.S. ’92, Ph.D. ’93 Arrives with Drive, Talent, Powerful Story

By Tom Parisi

Yvonne Harris, NIU vice president of Research and Innovation Partnerships

Yvonne Harris, NIU vice president of Research and Innovation PartnershipsYvonne Harris has come home.

Harris first arrived at NIU as an older non-traditional student and single mother, not knowing exactly what calling she wanted to pursue.

She departed NIU in the early 1990s as a triple Huskie—having earned three degrees, including a Ph.D. in science, with an emphasis in molecular and cellular radiation biology.

After an impressive career at institutions in Chicago, Virginia and California, Harris returned to her alma mater in August to head up NIU’s substantial research enterprise.

The amazing transformation of Harris, who arrives with a diverse portfolio of experiences and a powerful story, is the stuff of perseverance and dreams. Her life is full of firsts, having gone from a first-generation college student to the first African American to serve as the university’s vice president of Research and Innovation Partnerships, a critical leadership position.

NIU President Dr. Lisa C. Freeman calls Harris “a proven leader with demonstrated success.”

“Moreover, Dr. Harris’ career exemplifies the transformative power of NIU and its distinctive mission focused on access, equity, discovery and regional engagement,” President Freeman says.

Learning by doing

Harris grew up in a hardscrabble neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. After graduating from South Shore High School, she progressed through a series of jobs over the next decade, working as a waitress, typist, executive secretary and legal secretary.

“Each job crystalized in me the need to keep going,” Harris says. “And because I was a single parent—I had been married but it didn’t work—I said to myself, ‘I’m not settling for this because I wouldn’t let my children settle for this.’

“I decided I was going to go back to school.”

It wasn’t easy. She first attended a Chicago junior college while still working. She had no car, so her days began well before the crack of dawn. After a trip to the babysitter, she’d work from 8 a.m. to 5:45 p.m., then head off to evening classes.

‘What’s an NIU?’

Later, she briefly moved on to the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle (now UIC). “I didn’t really know what a university was all about,” she says. “Listening to speakers at orientation, it was like a foreign language to me.”

Harris started there as an art major and did well in her classes, but the quarterly semesters didn’t mesh well with her work schedule. Then a friend asked her if she had considered NIU.

“I said, ‘What’s an NIU?’ ” Harris recalls. “Then I went to DeKalb to visit, and I loved it.”

At NIU, Harris was like a kid in a candy store. Still trying to figure out exactly what she wanted to do, she dabbled in anthropology, psychology, history and philosophy. Then came that first biology course, and the first lesson, when students peered through a microscope to examine their own red and white blood cells.

“My world changed,” Harris says. “Watching those cells float in solution, I never saw anything so beautiful.”

Finding her path forward

Harris ended up focusing her studies on biology and philosophy. She recalls “wonderful professors,” including the late Michael Gelven in philosophy and stalwarts of the biology department such as Arnie Hampel, Linda Yasui, Mike and Deborah Hudspeth, Jerrold Zar, the late Rick Johns and the late Tom Conway, who was one of her graduate mentors.

“Tom was fabulous,” Harris says. “I can’t tell you how many times I cried in his office. He would sit there patiently smoking his cigar, listening to my problems and say, ‘So what are you going to do?’ He forced me to put my emotions aside and figure out a good path forward.”

Harris hit her stride, and life was good. Then, in her senior year, she ran out of money.

Faculty members again helped her find a path forward. Take the graduate school entrance exam, they told her. While still an undergraduate, she says she was accepted to NIU’s Graduate School. That allowed her to work as a teaching assistant during her senior year to defray tuition costs.

Harris studied for another decade at NIU, earning her master’s degree and Ph.D. “I spent a lot of time stumbling. What helped shape me was becoming a teaching assistant because I had to teach others.”

Professor Yasui, who served on Harris’ Ph.D. committee, recalls Harris as a bright and determined people person who juggled family and academic responsibilities and stood out “because of her genuine interest in such a different array of topics”—from philosophy to art to biology.

Harris left an indelible impression on faculty members, Yasui says.

“As a human being, Yvonne really, truly is remarkable,” she says. “She always engaged people and is truly interested in everyone she meets. She also seems to be a person who can articulate and implement her vision, and she does it seamlessly.”

Touching the lives of students

After NIU, Harris conducted post-doctoral work as a research associate at the University of Chicago and at UIC, where she later got her first taste of administration, helping undergraduates apply for a summer research program.

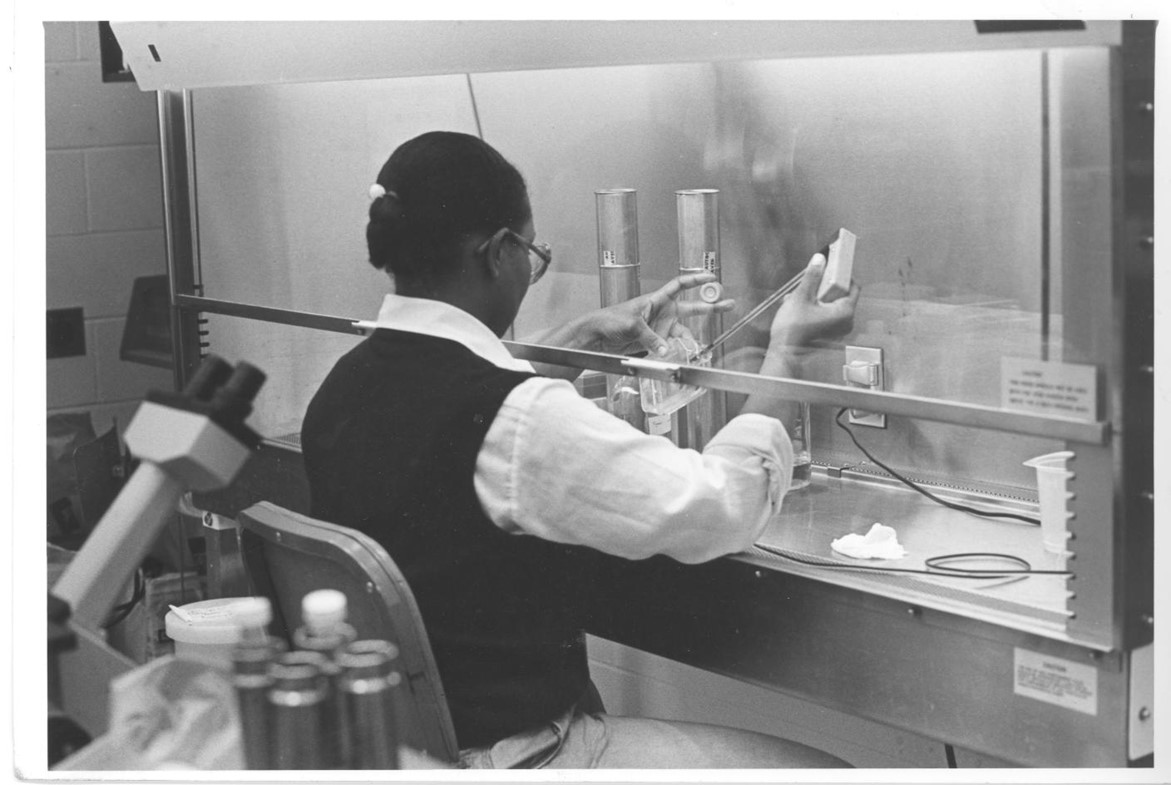

Some of the proudest moments of her career came later while on the faculty of Truman College, a community college in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood. Instead of establishing a lab for her own research, she created a biotech laboratory for students and a tissue-culture facility, the first of its kind at a community college in Illinois. Within a year, students were being trained in the use of state-of-the-art equipment, running molecular biology experiments and practicing tissue-culture techniques.

As a spinoff, she created a center aimed at increasing the number of underrepresented minority students in math and science. The center worked to remove the barriers to academic success that had historically plagued underrepresented students. Several of the center’s students went on to work for industry partners or to graduate programs where they earned their master’s degrees and Ph.D.s, Harris says.

“That was my biggest joy,” she says. “By that time, I’d become chair of the department and had further reach. Truman was in a marginalized community with students from all over the world. I could touch so many different students’ lives and loved it.”

Harris recalls one student in particular—Lynika Strozier. Harris mentored Strozier, who overcame a severe learning disability, earned two master’s degrees, inspired others and became a Field Museum scientist. Harris says Strozier was on the cusp of earning her Ph.D. when COVID-19 claimed her life in 2020.

Lynika was always told, ‘No, you can’t,’ and she didn’t understand why she could not,” Harris says.

“A child-development friend of mine once told me that people learn in different ways, and because of this, I developed my teaching style to incorporate the different ways in which people learn,” adds Harris, who believes it is human nature to observe and explore the world around us. “We’re all born mathematicians and scientists and capable of success.”

Crisscrossing the country

Harris rapidly progressed into larger roles at other institutions—dean of the Mathematics and Science Division at William Rainey Harper College in Palatine; associate vice president of the Office of Grants and Research Administration at Chicago State University; and vice provost of Research and Scholarship at James Madison University in Virginia, where she built a relationship with the governor’s office and contributed to a number of state initiatives.

Prior to coming to NIU, she served as associate vice president of Research, Innovation and Economic Development at California State University in Sacramento. There she restructured the Research Affairs Office, oversaw a $38 million sponsored projects portfolio and worked with the city and region on a wide array of issues surrounding inclusivity and workforce and economic development.

Building relationships, internally and externally, is among Harris’ strong suits.

“For me, I think there are three things I do well—collaborate, build partnerships and conduct outreach,” she says. “I am a person who is forever connecting the dots.

“In essence, research is about the creation of new knowledge,” she adds. “New knowledge is passed on to students through teaching, disseminated through scholarship and used to create innovations for the better good.”

Getting to know NIU—again

Harris has been spending her initial weeks at NIU getting to know faculty, staff and departments, as well as the university’s areas of research strength. She plans to help continue to develop research and innovation infrastructures and collaborate with faculty who mentor undergraduate and graduate student research.

“The long assortment of jobs in my life helped me learn that operational infrastructures are not fixed structures because people aren’t fixed structures,” Harris says. “You have to invest in people, which means providing mentoring, professional development and support. In this way, infrastructures evolve as people evolve.

“I’ve learned just how much I enjoy supporting and resourcing faculty researchers,” she adds, “and nurturing the next generation of talent.”

Harris, whose hobbies include painting and writing science fiction, is also excited to be back in the Chicago region, where she has relatives and friends and can be closer to her two daughters.

Not surprisingly, her daughters, like their mother, never settled for good enough.

Nile Aisha Harris earned a master’s degree in business administration at the University of Michigan. She recently served as a marketing executive for Abbott in Nashville and has her own consulting business. Cree T.C. Harris earned her engineering degree at Purdue and works as an industrial process engineer for CLIF Bar & Co. in Indianapolis.