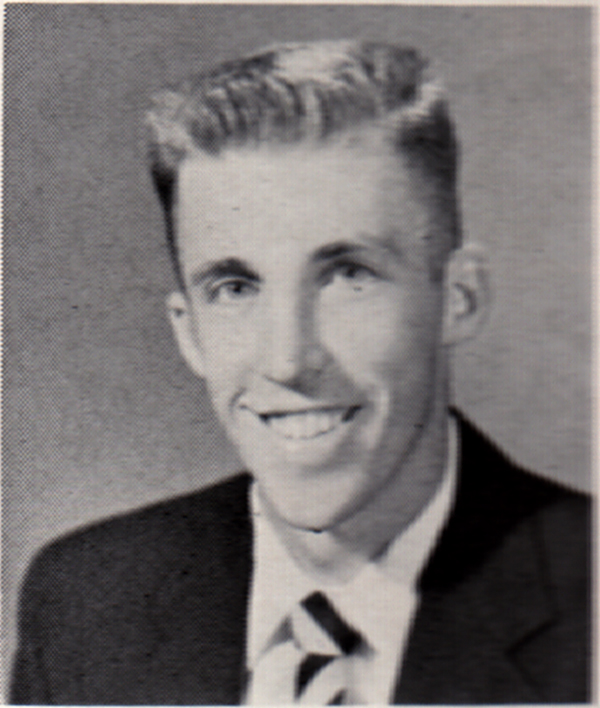

Physical Education alumnus Cal Korf takes a trip down memory lane six decades after his 1955 graduation from NISTC

“Dear Chairman McEvoy,” the note begins. “I just read your informative letter dated October 1, 2018. Congratulations on the program you are managing in Anderson Hall.”

Written by Cal Korf, the typewritten missive to Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education Chair Chad McEvoy came in response to an alumni e-newsletter sent to thousands of KNPE graduates.

Korf’s days in DeKalb were spent not at NIU, however, but at NISTC: the Northern Illinois State Teachers College. The enrollment at that time, he writes, “was barely two thousand students.”

“I will be 87 years old next month, but have wonderful memories of my four years at Northern Illinois,” Korf writes. “Most of my TKE classmates and members of the track and cross country teams are no longer among the living. The same status applies to ALL of my college roommates.”

The year was 1955, and Cal Korf was preparing to begin his career as a physical education teacher.

Korf had just completed his student-teaching hours at West High School in Rockford, the big city a few miles east of his small hometown of Winnebago.

His timing was perfect. He was fortunate enough to accompany legendary Coach Alex Saudargas and the boys basketball team “downstate” to win the 1955 Illinois State Championship, a feat Rockfordians continue to celebrate nearly 65 years later.

And he’s got a great yarn about that trip, one that involves the coach’s pregnant wife, the plan to have the team name the baby who was born during those finals and how the cheerleaders insisted that they were the ones to draw a name from the hat when Alice gave birth to a girl.

But Korf’s biggest story was yet to begin when he graduated from the Northern Illinois State Teachers College.

It’s a tale about what he did with his life – the spoiler is that he never did teach Physical Education – and how four years in DeKalb prepared him for a life of adventure around the world that he once had tried to avoid.

“During the Korean War, my roommate signed up for the National Guard. He said it was a really good deal. You get paid; you go to meetings now and then. But then his unit got activated, and he went to Korea. I said, ‘Holy moly.’ That was my sophomore year,” Korf says.

Two years later, as his 1955 commencement drew near, he felt confident that military service was not coming next.

“A government agency had come around and given everybody a test. If you passed, and you were guaranteed to graduate, you wouldn’t be drafted. I passed the test, and it wasn’t a candy test. Probably just a little more than half passed the test,” he says. “Well, in April of 1955, I got a letter from the Selective Service, and it said, ‘Do not seek employment.’ ”

Confused, Korf visited the U.S. Army Recruiting Station in Rockford. He knew the sergeant there: a fellow Winnebago High School graduate a few years older than he.

“He said, ‘Well, you’re a college graduate, so I can get you into the Counterintelligence Corps. That would require a three-year hitch. You’ll have to complete a comprehensive background investigation, and that takes time, but I’m sure that won’t be a problem,’ ” Korf says. “I had to go into Chicago for a day-long interview. I had to write what was like a brief thesis. Everything passed, and I reported to the Draft Board to go into active duty.”

Arriving at Fort Leonard Wood for basic training, he saw a familiar face.

“Lo and behold, there was my college roommate, Moose Krupke. He was the center on the football team, and he and I had played baseball together,” Korf says. “What a small world.”

By December of 1955, Korf had graduated again and was waiting for his first assignment. When the command announced that it needed two students to transfer to Monterey, Calif., to learn Czech, “I raised my hand and said, ‘I’ll take it!’ ”

As his three-year commitment eventually grew into 25 years, he first was stationed in Germany, where he worked with Czech refugees, translated articles in the Rudé právo newspaper for his higher-ups and became “pretty fluent” in the foreign tongue.

Following his graduation from Officers School, and his commissioning as a second lieutenant, he moved to Washington, D.C. to serve in the 116th Intelligence Corps.

When the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, Korf returned to Germany for the second of his three tours there.

“Being assigned to Berlin was probably the greatest assignment of my career,” he says. “There were spies on every corner, and I was involved in some top secret things. We captured a Russian colonel who tried to recruit one of our people.”

His next assignment brought him back to Washington, where he served in a premier intelligence unit with a global mission.

“Shortly after that, we had a big investigation going on in Paris, and the intelligence unit in Paris said it was more than they could handle, so it was tasked to our unit,” Korf says. “An Army sergeant had given the Russians all of our crypto equipment, so they had been able to review every top secret document coming through NATO for a period of months.”

Korf’s Army career took him back to Germany for a third and final time; to Bangkok, where he served for almost three years; through two tours of duty in the Vietnam War; back to Paris for a six-month temporary assignment; and again to D.C.

It was there, as a lieutenant colonel, that he accepted his final transfer – to Hawaii.

His commanding general in the Aloha State gave him an important duty regarding a GS-12, a civilian employee equivalent in rank and salary to a U.S. Army major. “He said, ‘A crook’ – he actually used that term – ‘he runs the museum. I want to get rid of him, but I don’t want to have to take him back on appeal, so you’ll have to do a thorough investigation.’ ”

Five months later, as Korf watched that GS-12 emerge from a Hawaii courthouse with “his head down to his chest,” he knew he’d done well.

That general and Korf had become good friends, meanwhile, and Korf was able to name his next responsibility. He wanted to manage the Army’s trio of golf courses in Hawaii, a request that raised the eyebrows of his boss.

“There are five lieutenant colonels who have applied and are vying for that position,” the general replied. “It’s an important job – the previous person did a terrible job, and there are a lot of things to be cleaned up – but it’s not career-enhancing.”

Korf smiled. “I said, ‘When I’m finished here, I’ll have 25 years, and I intend to retire.’ And he said to me, ‘By God, I’ve got a square peg for a square hole.’ ”

No residence halls existed when Korf arrived at NISTC. “That was probably a good thing,” he says with a laugh.

“I was in an apartment – it was in a home – and I had to ride my bicycle from there over to school, so I didn’t really get involved in social activities,” he says. “Jimmie’s Tea Room was the big hangout for everyone in school, and they always had a big wipeout after every semester. Had I lived on campus, I might have been at one of those instead of doing my homework.”

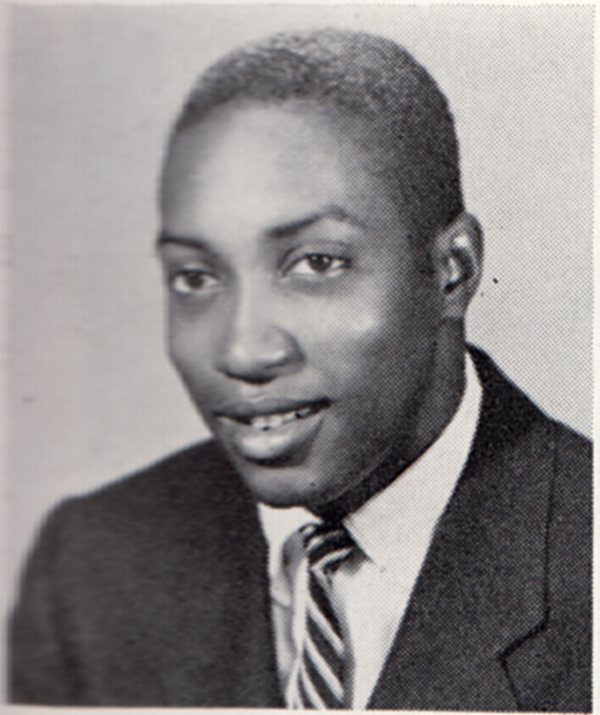

Also in short supply were faces of color. Korf could count the number of African-American students on one hand; among them was Ted Wright, Korf’s sophomore-year roommate at the newly opened Gilbert Hall.

Before the pair became roommates, however, Korf had an encounter that today is unimaginable.

“The Dean of Men met me at the entrance coming in to register. He said, ‘I’ve assigned Ted Wright as your roommate. Do you have a problem with that?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t have a problem,’ ” Korf says.

“As a matter of fact, we were on the track team together. We were on the cross country team together. We played intramural basketball together. He had played at DuSable High School in Chicago and was a good basketball player,” he adds. “I took Ted home to Winnebago some weekends. I took him to our summer home in Madison. My mother treated him like one of her own.”

Most of his DeKalb memories, though, focus on sports.

A self-professed “jock all the way through high school,” Korf was inspired by his high school basketball coach to study Physical Education, even if the coach had urged him to become an undertaker instead.

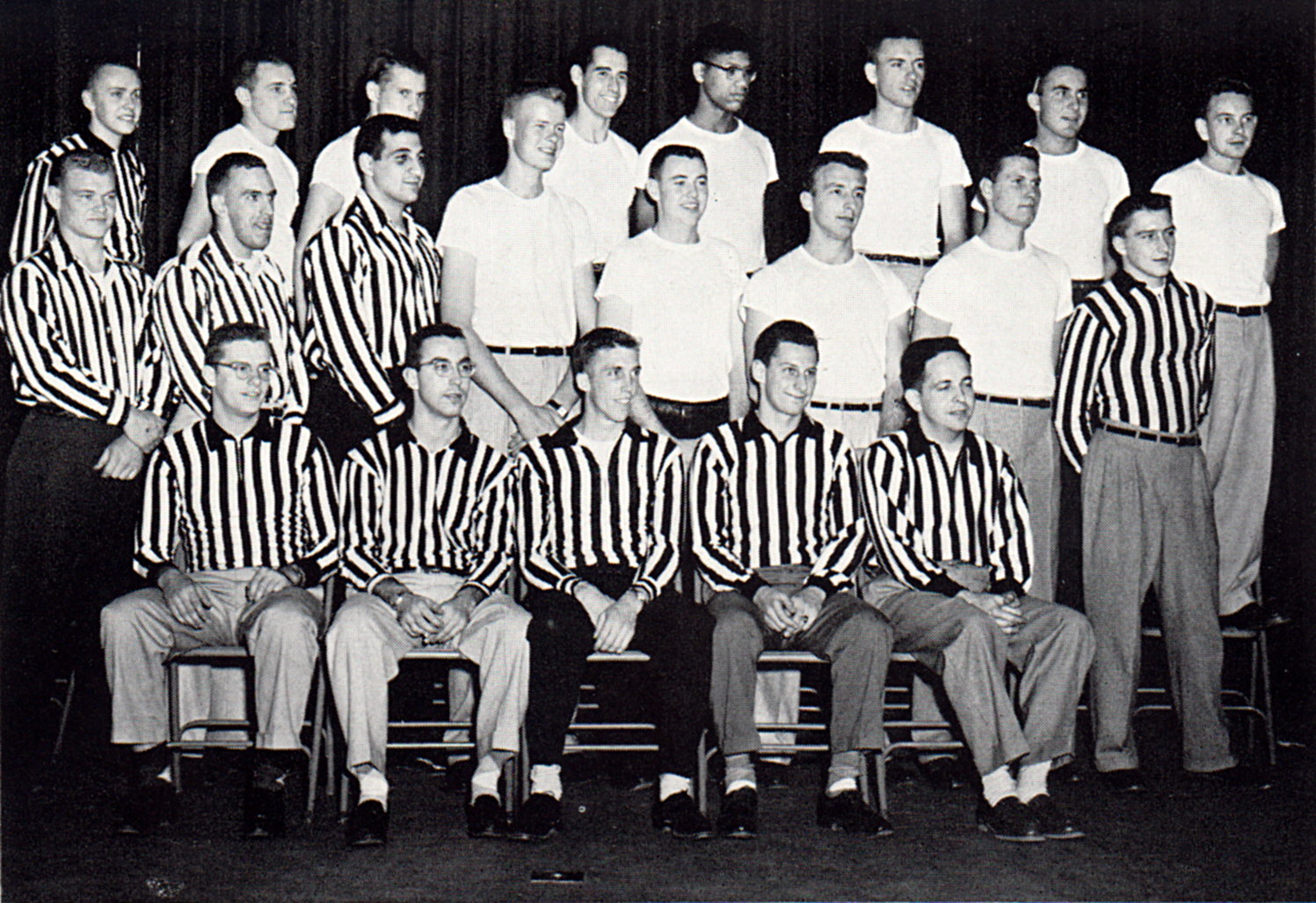

Gil Hertz, coach of the NISTC men’s basketball team, had made it clear that anyone wanting to try out for the squad should train with the cross country team during the fall.

“I was always ultra-competitive, so when they had a cross country race, I finished second. The coach said, ‘Draw your uniform,’ and I said that I was only there because of basketball. He said, ‘I’ve already talked to Coach Hertz, and if you don’t run on the team, then you’ve already been cut from the basketball team,’ ” Korf says.

Korf joined the team, as well as the track team, where he thrived for four seasons under legendary coach and NIU Athletics Hall of Famer Carl Appell. Ironically, he never played basketball.

On track, he ran the quarter-mile for all four years, anchored the mile relay and, when needed, ran the 440, the half-mile and the mile.

Appell, who also taught Kinesiology courses, was a taskmaster in and out of the classroom.

When one sprinter skipped practice without permission to attend a birthday party, for example, Appell showed no mercy the day after.

“Carl said, ‘Where were you last night?’ He said, ‘A birthday party at Jimmie’s Tea Room.’ Carl said, ‘Turn in your uniform. You’re no longer on the track team,’ ” Korf remembers. “The guy started crying, saying, ‘Don’t do this to me. Don’t do this.’ Carl didn’t flinch. You think anybody missed a practice after that?”

Korf tested those waters himself, however, during the weekend of an indoor track meet in Chicago.

“It was maybe my sophomore or junior year. I told Carl, ‘Well, we’ve got an intramural basketball tournament, and the TKE team is going to be in the semifinals and maybe the finals.’ I said that I really needed to play; that if I didn’t play, they didn’t have a chance,” he says.

“I ended up driving into Chicago, and I showed up early in the morning to get ready, and Carl said, ‘I’m glad to see you here. I think there’s a chance that maybe you will mature,’ ” he adds. “He was a tough, tough guy. He was probably the best instructor I ever had – period – through my military life or after.”

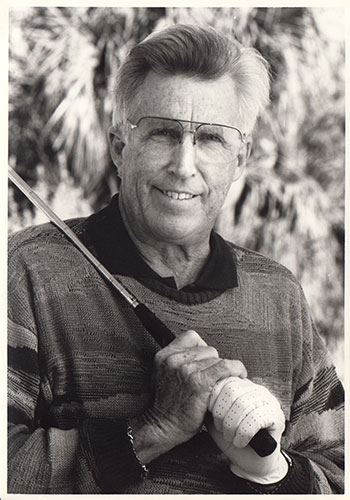

Florida beckoned Korf and his wife, Karen, after military life came to an end.

The couple settled in Sarasota, where Korf – fresh from his management of the U.S. Army golf courses in Hawaii – discovered the Florida State Golf Association. Its executive director was about to retire and, Korf says, the organization’s finances were in disarray with “only enough money in the checking account to keep the account open.”

Despite that, Korf tossed his name in the hat.

“I knew there wasn’t any money. Several of the people who applied were asking for $35,000 or $45,000 as a starting salary; I had volunteered and ran the association for two months during the summer, and I knew there wasn’t any chance for a salary like that,” he says.

“When I had my interview, I addressed the board and I said, ‘I know what the financial situation is here. I will take the job for $1,000 a month and do that for six months. If you’re satisfied, then we will renegotiate and do a real contract. If you’re not happy, you won’t have lost much by then, and you can just take one these other guys,” he adds.

“The vice president said, ‘I like that idea!’ Fortunately, I got the job, and I did that for 17 years. We grew it into a pretty good organization. It’s now the largest in the country.”

After his second retirement, the mailbox promptly brought another opportunity – and, although not apparent at the start, Career No. 3.

Korf had received a letter inviting him to join the Berlin U.S. Military Veterans Association, which he did. Soon afterward, he got a phone call from the group’s president. The secretary had died, the president said, opening that position. Would Korf take it?

“I said, ‘Well, I’ve just retired from my civilian job, and yeah, I could do that,’ ” he says. “They were struggling. They didn’t have 600 members at the time. At the annual meeting, I said, ‘I’ll take over the membership committee.’ ”

He phoned a general he knew from Vietnam to offer him a complimentary membership in the Berlin Veteran Association with an ulterior motive: to solicit membership from all of the general’s “people.”

The strategy continued on to other generals and, one year later, membership already had soared to more than 2,000.

Yearly reunions took place in Berlin, but when Korf heard that some veterans had to borrow money to attend, he decided to host the get-togethers every four years in Germany with U.S. locations in between.

He also was inspired by that situation to coordinate and offer after-reunion bus excursions around Europe to make the trips to Berlin worth the cost for the members. Destinations include Belgium, Budapest, Ireland, Italy, Normandy, Paris, Prague and Vienna. His final tour took place in 2017.

Now retired for good, and living in Nokomis, Fla., Korf still thinks about NIU and even stays up late to watch Huskie football battle on ESPN.

“I could’ve washed out as a freshman, like so many did, but I was involved in all of the sports and everything else,” he says. “I matured and grew up in my time there.”

Note: this article originally appeared on the NIU College of Education website.